Dr Zyra Evangelista & Professor Ellen Boeren

Global and technological developments in the past three decades underscore the need for adults to continue learning throughout their lives. Promoting participation in lifelong learning is increasingly important to support individuals in adapting to perpetually evolving and rapidly changing economic, work, and socio-cultural environments. During the 2010s, participation in adult learning and education went in decline. Triggered by the need to unpack this observation in more detail, we started the ESRC project ‘A UK-Ireland investigation into the statistical evidence-base underpinning adult learning and education policy-making’.

During the last year, using data from Learning and Work Institute’s annual Adult Participation in Learning (APiL) Survey, we investigated trends in participation in adult learning and education (ALE) in the UK from 2002-2023. We recently launched our report during a webinar. You can find both outputs online.

How have UK ALE participation rates varied from 2002-2023?

Research on adult education typically starts with the vital question, ‘what is an adult?’ Our project is primarily interested in adults who left initial education and who then keep on learning or return to learning at a certain point in their lives. This can be in credential-based formal education, in non-formal training interventions, or can be rather informal through online learning at home. We therefore concentrated on adults between the ages of 25 and 64. Before Brexit, this age group was also the focus of the European adult education and training benchmark.

APiL data allowed us to work with a sample of 67,787 adults aged between 25 and 64. And indeed, we found that ALE participation rates in the UK have steadily declined in the run up to the pandemic, especially during the 2010s. For our specific target group, we found a baseline participation rate of 44.3% in 2002 and reaching a low of 31.9% in 2019. This participation rate is based on current (i.e. adults taking part in ALE at the time of the APiL survey) and recent (i.e. adults who took part in ALE in the last three years) participation.

To some extent, the decline in participation rates coincided with macro-level austerity measures in the aftermath of the financial and economic crash during the late 2000s. For instance, the 2010s were characterised by lower trade union membership and employer investment in training, and a rise in zero-hour contracts.

Interestingly, ALE participation rates for those between 25 and 64 rose post-pandemic – reaching a high of 53.4% in 2023. More research is needed to fully understand this pre- and post-pandemic shift. However, potential explanations include the rise in flexible working patterns and government support for reskilling and online learning. It is also worth mentioning that the APiL survey’s data collection mode shifted to a completely online one. Such changes in data collection can inevitably influence the results (see Blog 1).

How have ALE participation rates varied by UK region?

APiL is a representative UK survey and collects data among all corners of the UK.

Among the four devolved nations, during the period 2002 – 2023 Wales averaged the highest participation rate (42.9%), followed by England (41.3%), Scotland (38.7%), while Northern Ireland had the lowest participation rate (37.1%).

Looking at English participation rates in more detail, all English regions had participation rates over 40 percent. Overall, the South West of England averaged the highest participation rate (44.9%); while the East Midlands averaged the lowest (40.0%).

Regional variations can potentially be attributed to national differences in ALE policies, as well as differences in the socio-demographic profiles across regions. For instance, Scotland and Northern Ireland had lower proportions of adults from the highest social grade AB and higher proportions of adults who left full-time education before the age of 21. Below, we will explain that ALE participation patterns strongly vary according to socio-demographic and socio-economic characteristics such as social grade and age left full-time education.

Who is most likely to participate in ALE in the UK?

Overall, younger adults who finished full-time education at or after age 21 – a proxy we had to use for educational attainment given the absence of this variable -, belonging to the highest social grade AB (i.e. higher & intermediate managerial, administrative, professional occupations), and are in full-time employment had the strongest probability of taking part in ALE.

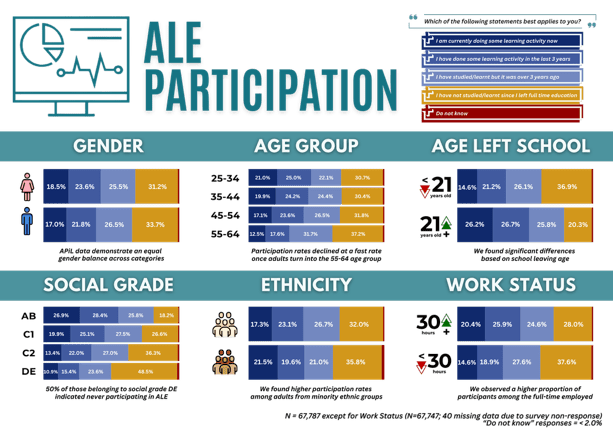

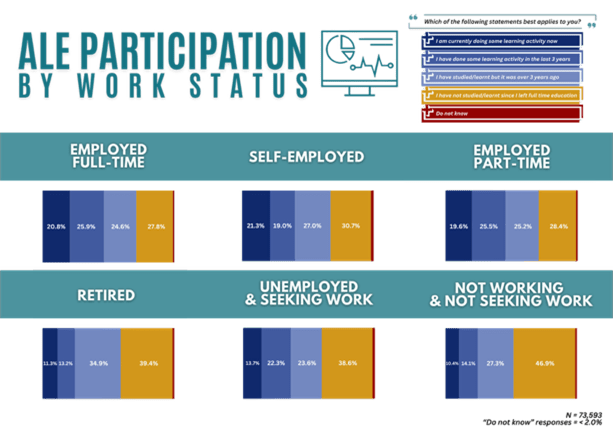

In line with the literature (see also Figure 1a), we found that younger adults were more likely to participate and that rates rapidly decline by age 55-64. Middle class adults were more likely to participate too. Among those in the lowest social grade (DE), nearly half of them had never participated since leaving school. In terms of school leaving age, adults who left full-time education at age 21 or above were more likely to participate in ALE than those who left full-time education before age 21. As seen in Figure 1b, for work status, adults who were employed were almost twice as likely to participate in ALE compared to those who were not employed. This is not surprising given that job-related learning constitutes a significant part of adult learning. Patterns for gender and ethnicity were less clear cut. Although women were more likely than men to participate in ALE, this difference was marginal. Likewise, adults from minority ethnic groups were more likely to participate in ALE than their white counterparts, but this difference was marginal and needs to be treated with caution given the uneven sample composition.

As shown in Figure 2, those in the high-advantage group (age 25-34, social grade AB, left full-time education after age 21, full-time employed) had about 70% chance of taking part in ALE compared to less than 20% chance among the low-advantage group (age 55-64, social grade DE, left full-time education before age 21, not full-time employed). These socio-demographic patterns highlight entrenched inequalities in ALE participation, especially by age and social grade. However, after taking these socio-demographic characteristics into account, it is interesting to note that previous participation in ALE appeared as the strongest predictor for adults’ future participation intentions. This suggests the cumulative effect of participation – i.e. it seems that learning begets more learning.

Why do adults in the UK take part in ALE?

For those who participated in adult learning and education during the last three years, we had access to data on their motivations and benefits associated with ALE participation. These were a mix of career-related/monetary reasons and personal development/non-monetary reasons.

The top three motivations for ALE participation were: self-development (32.7%), improving job skills (29.7%), interest in the subject (29.6%). Notably, the following socio-demographic categories were more likely to indicate that their participation in ALE was involuntary (i.e. ‘not really my choice’): older adults, those who left full-time education before age 21, those from social grade C2, white adults, and adults in full-time employment.

The top three benefits from ALE participation were: improving job skills (27.6%), enjoying learning more (24.4%), improving self-confidence (22.4%). Interestingly, the following socio-demographic categories were more likely to express a lack of perceived benefits from ALE participation (i.e. ‘I have not yet experienced any benefits or changes’): older adults, those from lower social grades, white adults, and adults who are not in full-time employment.

What hinders adults in the UK from taking part in ALE?

Adults can experience various challenges and barriers that either hamper or prevent their participation in ALE. Again, APiL provided us with data to investigate such issues, more specifically on barriers for non-participants and challenges for participants.

Interestingly, the top three challenges and barriers were similar across learners and non-learners. Among adult learners, the top three challenges they encountered while learning were: nothing/none (40.0%), work/time pressures (21.5%), cost/money (11.2%). While among adult non-learners, the top three barriers that prevented them from taking part in ALE were: nothing (36.7%), work/time pressures (21.8%), cost/money (20.0%).

What is notable is in both cases ‘nothing’ came out as the top challenge and barrier. For adult learners, this option was selected more often by older learners. For non-learners, this option was more likely to be selected by men and those in the older age categories. Especially for non-learners, the high proportion of adults who opted for ‘nothing’ needs further attention, as it indicates that participation in learning is not on their radar.

How did the COVID-19 pandemic impact ALE motivations, challenges, barriers?

APiL data allowed us to compare the pre-pandemic years (2017-2019) and post-pandemic years (2021-2023) and we found the following trends:

For motivations, during the pre-pandemic years, around 80 percent of adult learners indicated work/career reasons as their main motivation for learning compared to approximately 20 percent who indicated leisure/personal interest as their main motives. This 80-20 split in favour of work-related reasons shifted to a 60-40 split in the post-pandemic years.

For challenges,a higher proportion of adult learners indicated encountering challenges after the COVID-19 pandemic as every single challenge category had higher rates post-pandemic compared with the pre-pandemic years.

For barriers,a higher proportion of adult non-learners selected barriers preventing their participation after the COVID-19 pandemic. During the pre-pandemic years, ‘nothing is preventing me’ was indicated by 45 percent of respondents but this declined to 25 percent during the post-pandemic years. Interestingly, we also found a significant increase for the barrier option ‘I feel I am too old’ to participate, which rose from 6 percent in the pre-pandemic years to over 20 percent in the post-pandemic years.

While these findings give us initial pointers on the potential changing dynamics of adult learning, these observations need more in-depth investigations in future years.

How can we improve ALE participation in the UK?

Our research revealed ongoing inequalities in participation to adult learning across the UK, especially in relation to socio-economic and socio-demographic background characteristics such as age of leaving initial education and social grade. Participation also rapidly declines by age.

These insights allow us to recommend the need for ongoing efforts to lower barriers to learning. This includes actions to lower cost barriers for the most vulnerable groups and to allow adequate time for learning within the work-life balance. But it also needs acceleration in efforts to reduce such gaps from an early age onwards given inequalities carry on over the life cycle. In doing so, it will be important to value learning both for job-related purposes and for personal growth and development.

Finally, we recommend expanded research agendas to better understand (non)learner profiles and experiences. There is still a lot to unpack around why people choose to engage in ALE and why they don’t. We are calling for more mixed-method, longitudinal research to delve deeper into what motivates adults to learn, what gets in their way, and what they get out of ALE over the life cycle. The better we understand ALE motivations, benefits, challenges, and barriers, the more we can design useful policies and programmes to support lifelong learning for everyone.