Dr Betul Babayigit, Dr Sharon Clancy, Professor Ellen Boeren

The Background for the ESRC-Lifelong Learning Project

The participation rates in adult learning and education (ALE) are decreasing. The number of publicly funded qualifications started by adults has declined by 70% since the early 2000s, dropping from nearly 5.5 million qualifications to 1.5 million by 2020 (Tahir, 2023). Total participation to further education and skills in 2021/22 decreased by 23.2% compared to 2016/17 (Skills Funding Agency & Department for Business, Innovation and Skills, 2023). In the face of this severe decline, the need for effective policymaking in ALE, aiming at involving more individuals in learning, is starker than ever. Policymaking is usually constrained by politics, finance, and time limitations (Campbell, et al., 2007; Oliver et al., 2014). However, policies based on evidence are ‘likely to be better informed, more effective and less expensive’ (Campbell et al., 2007, p. 15) than policies formulated through ordinary time-constrained and politically constrained processes (Strydom et al., 2010). In this regard, the quality, validity, and reliability of evidence become major factors in predicting the effectiveness of evidence-based policymaking. Therefore, within the scope of our ESRC-funded project, we aim to investigate the statistical evidence base underpinning adult education policies. By taking the Learning and Work Institute’s (L&W) Adult Participation in Learning (APiL) survey as our focus, we attempt to generate new knowledge on the nature of statistical data on adult learning and education and its potential uses for evidence-based policy making in the devolved nations of the United Kingdom and the Republic of Ireland.

In the first part of the project, we scrutinise the existing surveys in the field of adult education, especially the APiL survey of the L&W since it is the longest-running and most frequent and consistent UK study of participation in adult education. So far, we have examined the questions used in the APiL survey through a document analysis in addition to the data sets generated by it and have also conducted in-depth interviews with its developers and other researchers who have worked on the survey, to better understand its evolution and the variations in questions and answering categories. Further analyses will include a quantitative comparison of surveys that provide data about adult participation in learning in the UK context. This comparison will reveal potential differences in participation rates across surveys in relation to their definitions of learning and their reference periods. In later phases of the project, we will analyse the participation trends in the last 25 years in relation to the individual level determinants of participation and attempt to explain these trends in relation to societal events and political shifts. The last phase of the project will unpack the adult education discourses in the policy agendas of the devolved nations and the Republic of Ireland by shedding light on how they construct these discourses and how they benefit from the statistical evidence in their policymaking process.

One impetus that led us to do this research project is the depiction of the existing data for participation in adult education as ‘not being of reasonable quality’ (Felstead et al., 1997, p. 12) or being insufficient and poor (Kuper et al., 2016; Widany et al., 2019). The quality of the data in adult learning is likely to be caused by survey errors, which can be described as ‘any error arising from the survey process that contributes to the deviation of an estimate from its true parameter value’ (Biemer, 2016, p. 122). While discussing survey errors, we might benefit from ‘The Total Survey Error (TSE)’ paradigm, which refers to all errors that may arise from the design, collection, processing, and analysis of survey data (Biemer, 2010). From the TSE perspective, the most salient reasons can be regarded as coverage errors, sampling errors, nonresponse errors, validity issues, measurement errors, and processing errors (Groves et al., 2009; Groves & Lyberg, 2010).

A possible source of error in measurement can be the anchoring and adjustment effect (AAE), a prominent cognitive bias that can cause deviations from the actual participation rates in adult education and learning by altering respondents’ perceptions about what counts as learning. The data-distorting implications of this cognitive bias for validity and reliability issues in various subdisciplines of educational sciences have been widely discussed (Bard & Weinstein, 2017; Osterman et al., 2018; Zhao & Lindenholm, 2008); however, it is difficult to come across such studies in the field of adult education. Therefore, we aim to introduce this issue to the domain of adult education, drawing upon an illustrative case from the Learning and Work Institute’s APiL survey. By doing so, we aim to demonstrate how earlier questionnaires distributed by market research companies may inadvertently bring about substantial errors in adult education participation statistics. Our intention is to bring this concept to the attention of scholars and research bodies concerned with adult learning, with the hope of contributing to the development of robust measurement tools designed to measure participation rates in learning as the robustness of measurement can have a substantial impact on the effectiveness of evidence-based policymaking.

The Adult Participation in Learning Survey and the Anchoring and Adjustment Effect

The Learning Divide (Sargant et al., 1997) of the L&W, formerly NIACE, and the subsequent survey The Learning Divide Revisited (Sargant, 2000) can be considered as the starting points for the APiL survey. Begun to collect data in 1996, the APiL survey annually asks – with a few exceptions in some years – over 5000 adults aged 17 and above about their participation in learning in addition to a number of crucial aspects of adult education such as the motivations of learners and the barriers hindering participation. The data collection process of the APiL survey is carried out by a market research company through an omnibus survey, a survey model that research companies use to collect data about various topics in a single interview usually for different organisations. The data for APiL was collected face-to-face until the pandemic forced the polling industry to reach the participants through telephone interviewing in 2020. Since 2021, the APiL data has been collected through an online survey.

The APiL survey has two core questions that are constantly asked each year. The first question measures ‘whether the respondents see themselves as learners’ (Interview – Fiona Aldridge, 27th October 2023) by asking them whether they have been involved in any learning activity in the last three years, while the second core question asks about respondents’ intentions to learn in the future. The participation question of the APiL survey is preceded by a broad definition of learning, which also serves as an ‘anchor’, implicitly encompassing all forms (formal, nonformal, and informal) and domains (cognitive, affective, and psychomotor domains) of learning to arouse respondents’ memories of learning.

‘Learning can mean practising, studying, or reading about something. It can also mean being taught, instructed, or coached. This is so you can develop skills, knowledge, abilities or understanding of something. Learning can also be called education or training. You can do it regularly (each day or month) or you can do it for a short period of time. It can be full-time or part-time, done at home, at work, or in another place like college. Learning does not have to lead to a qualification. We are interested in any learning you have done, whether or not it was finished.’ (Hall et al., 2022, p. 6)

Following the presentation of this broad definition of learning, the APiL survey investigates whether the respondents have been involved in a learning activity in the last three years by using this question:

‘Which of the following statements most applies to you?

01: I am currently doing some learning activity now

02: I have done some learning activity in the last 3 years

03: I have studied\learnt but it was over 3 years ago

04: I have not studied\learnt since I left full time education’ (Sargant & Aldridge, 2002, p. 119)

As seen from above, the participation question of APiL covers a relatively long period of time and it might require a considerable amount of cognitive effort for respondents to remember the learning episodes they were involved in. Questions about participation in adult learning innately relate to the past and require respondents’ recalling the learning event, and an extended reference period might cause increased memory problems (Groves et al., 2009; Widany et al., 2019). In this sense, the L&W’s definition of learning can be very useful in triggering respondents’ memories of learning and eliciting more accurate information by reducing the amount of cognitive effort and memory issues.

From this perspective, the learning definition of the APiL survey can be regarded as an ‘anchor’. Anchors are defined as the initial pieces of information that are intended to form a base for the subsequent answers of respondents (Tversky & Kahneman, 1974). Although the use of anchors can have some benefits, such as reducing cognitive effort and facilitating recall of a piece of information that is hard to remember, it also has the potential to cause systematic errors in measurement by leading to biases or fallacious decision-making, which is called the anchoring and adjustment effect (Akbulut et al., 2023; Tversky and Kahneman, 1974). The anchoring and adjustment effect (AAE) can be described as a common human tendency to rely too much on an initial piece of information presented when making subsequent decisions (Chen, 2010). Tversky and Kahneman (1974) coined the term during their seminal experiment, where they asked their participants what percentages of African countries were in the United Nations. Prior to responding to this question, participants were asked to guess whether the percentage was higher or lower than a number randomly appearing on a spinning wheel. When the figure ’10’ appeared on the wheel, students gave an average estimate of 25% in contrast to 45% when the wheel came up with the number ’65’, always converging to the initial figure on the wheel. Although the numbers on the wheel were purely arbitrary in nature, they served as powerful ‘anchors’ that significantly influenced participants’ ‘adjustment’ behaviour which refers to making biased decisions under the influence of an anchor and therefore possibly deviating from the true value (Tversky & Kahneman, 1974; Zhao & Linderholm, 2008).

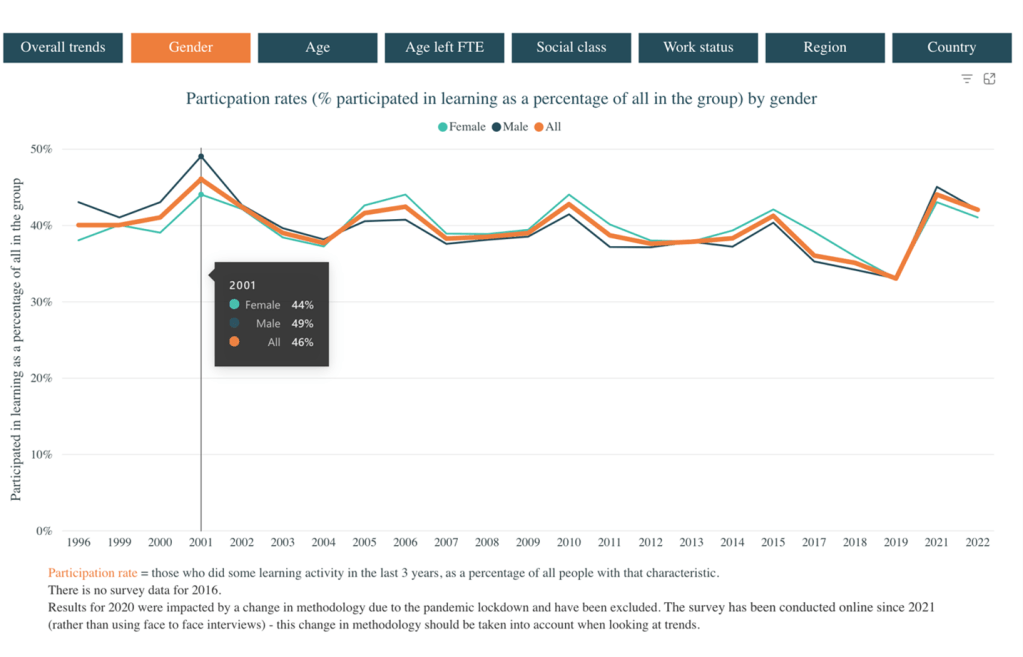

A potential incidence of AAE may have happened in 2001’s APiL survey according to Prof. Sir Alan Tuckett, who served as the chief executive of NIACE between 1988 and 2011 and took on a primary role in designing the APiL survey in collaboration with other key scholars such as Naomi Sargant and Fiona Aldridge. While we were interviewing him, Tuckett specifically mentioned the 2001 survey, which yielded the highest participation rate (46%*) in APiL’s history, by saying:

‘The highest response to participation was in 2001. And why? Because our suite of questions on the market research questionnaire followed directly on questions about sport. Since people became sensitised by the earlier range of questions, when they came to our questions, more of them saw a connection.’ (Interview – Tuckett, 4th October 2023)

As seen from Tuckett’s quote, the respondents of the APiL survey in 2001 were sensitised by a prior survey about sports activities. Although people ‘did not see sports as learning’ in those days, in Tuckett’s words (Interview – Tuckett, 4th October 2023), the respondents might have thought that their involvement in sport activities could be counted as learning due to the anchoring effect of the previous survey. Under the influence of the anchor, respondents may have adjusted their answers andtended to say that ‘they had learned something in the last three years’, more than if they had not participated in the previous survey. In other words, respondents might have deviated from the ‘true’ answers which they would have given in the absence of the previous sports survey. Therefore, the learning rates in APiL 2001 could have been overstated due to the potential AAE of the survey preceding APiL. The problem with AAE is that once the data is collected, it is quite challenging to trace back the influence of AAE or undertake analysis to obtain evidence for or against its existence. Therefore, we may not assert that the spike in participation rates in 2001 was caused by the AAE, but we cannot eliminate this possibility either.

An interesting point is that although the APiL survey utilises an initial anchor, the learning definition that the L&W has been constantly using since initiation of the survey for comparability reasons, a previous anchor from another survey might have been more influential on the answers of the APiL respondents. This specific incident in 2001 might show that a previous anchor can interact or counteract with the designated anchor of a subsequent survey, affecting the accuracy and the data quality. The possibility of AAE having happened in other rounds of APiL or in other surveys that measure adult participation in learning might cast a shadow over the existing statistical evidence base in adult learning that is already laden with various problems, such as the insufficient coverage of ethnic minority groups (Interview – Emily Jones, 13th October 2023) and low degree of comparability with other surveys (Widany et al., 2019). Another possibility is that the APiL survey itself might have provided a prior anchor to the respondents other than its usual learning definition in some years. For example, the survey in 2002 started with an inquiry about leisure time activities such as gardening, indoor games, and physical activities (Sargant & Aldridge, 2002), which might have led to another AAE and caused participants to deviate from their original answers. However, it should be noted that this is only a possibility that is almost impossible to confirm or refute. Not being able to test or trace back whether AAE interfered with other measurements of either the APiL or the other adult education surveys further complicates the data quality issue in measuring adult participation in learning and calls for the attention of adult education survey designers in their future work.

One might easily think that the anchors are data contaminators and should not be used. However, refraining from using them may not even be possible, as the respondents might generate their own anchors (Gehlbach & Barge, 2012) while going through a single survey. Therefore, the smart use of anchors and avoiding misleading anchors may be more plausible, especially when we consider the complexity of recalling a learning instance that happened a long time ago. Since the core participation question of the APiL survey covers a three-year time span (‘I have done some learning activity in the last three years’), the use of an effective anchor becomes even more of a necessity. Using a cleverly designed anchor supported by visual aids such as lists on a show card might be useful in arousing the respondent’s memories of learning, resulting in more accuracy in measurement (Widany et al., 2019). Conducting a small-scale randomised trials on the effectiveness of such anchors prior to a large-scale survey and improving the anchor accordingly may result in more accurate future responses and ultimately increase the methodological robustness of the measurement. In our series of blogposts, we will next compare the available surveys in ALE that collect data from the UK context and further scrutinise the statistical evidence base underpinning ALE, hoping to contribute to the methodological discussions in the field.

*The highest participation rate in APiL survey was captured in 2023 by 49%. However, both the interview with Tuckett, Aldridge and Jones and the write-up process of this post was completed before the release of the APiL 2023 report.

References

Akbulut, Y., Saykılı, A., Öztürk, A., Bozkurt, A. (2023). What if it’s all an illusion? To what extent can we rely on self-reported data in open, online, and distance education systems? International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 24(3), 1-17.

Bard, G., & Weinstein, Y. (2017). The effect of question order on evaluations of test performance: Can the bias dissolve? Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 70(10), 2130–2140. https://doi.org/10.1080/17470218.2016.1225108

Biemer, P. P. (2010). Total survey error: Design, implementation, and evaluation. Public opinion quarterly, 74(5), 817-848. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfq058

Biemer, P. (2016). Total survey error paradigm: theory and practice. In Wolf, C., Joye, D., Smith, T. W. and Fu, Y. (Eds.), The SAGE Handbook of Survey Methodology (pp. 122-141). SAGE Publications Ltd. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781473957893

Campbell, S., Benita, S., Coates, E., Davies, P., & Penn, G. (2007). Analysis for policy: Evidence-based policy in practice. London: Government Social Research Unit. https://issuu.com/cecicastillod/docs/pu256_160407

Chen, P. H. (2010). Item order effects on attitude measures. [Doctoral thesis, Morgridge College of Education]. University of Denver Digital Commons. https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd/778/

Felstead, A., Green, F., and Mayhew, K. (1997). Getting the Measure of Training. A Report on Training Statistics in Britain. Leeds: Centre for Industrial Policy and Performance; University of Leeds.

Gehlbach, H. & Barge, S. (2012). Anchoring and adjusting in questionnaire responses. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 34(5), 417-433. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01973533.2012.711691

Groves, R. M., Fowler, F. J. Jr., Couper, M. P., Lepowski, J. M., and Singer, E. (2009). Survey Methodology, 2nd Ed. Hoboken: Wiley.

Groves, R. M., and Lyberg, L. (2010). Total survey error: past present and future. Public Opinion Quarterly. 74, 849–879. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfq065

Hall, S., Jones, S. & Evans, S. (2022). Adult participation in learning survey 2022. Learning & Work Institute. https://learningandwork.org.uk/resources/research-and-reports/adult-participation-in-learning-survey-2022/

Kuper, H., Behringer, F., and Schrader, J. (ed.). (2016). Development of indicators and a data collection strategy for further training statistics in Germany. Bonn: Bundesinstitut für Berufsbildung. https://www.bibb.de/veroeffentlichungen/de/publication/show/8101

Learning and Work Institute. (2023). Rates of adult participation in learning. https://learningandwork.org.uk/what-we-do/lifelong-learning/adult-participation-in-learning-survey/rates-of-adult-participation-in-learning/

Oliver, K., Innvar, S., Lorenc, T., Woodman, J., & Thomas, J. (2014). A systematic review of barriers to and facilitators of the use of evidence by policymakers. BMC Health Services Research, 14, 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-14-2

Ostermann, A., Leuders, T., & Nückles, M. (2018). Improving the judgment of task difficulties: prospective teachers’ diagnostic competence in the area of functions and graphs. Journal of Mathematics Teacher Education, 21(6), 579–605. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10857-017-9369-z

Sargant, N., Field, J., Francis, H., Schuller, T., Tuckett, A. (1997). The Learning Divide: A study of participation in adult learning in the United Kingdom. Leicester: National Institute of Adult Continuing Education.

Sargant, N. (2000). The Learning Divide Revisited. Leicester: National Institute of Adult Continuing Education.

Sargant, N. & Aldridge, F. (2002). Adult Learning and Social Division: A Persistent Pattern, Volume 1: The Full NIACE Survey on Adult Participation in Learning 2002. Leicester: NIACE.

Skills Funding Agency & Department for Business, Innovation and Skills. (2023). Further education and skills. https://explore-education-statistics.service.gov.uk/find-statistics/further-education-and-skills/2021-22

Strydom, W. F., Funke, N., Nienaber, S., Nortje, K., & Steyn, M. (2010). Evidence-based policymaking: A review. South African Journal of Science, 106(5), 1-8. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajs.v106i5/6.249

Tahir, I. (2023). Investment in Training and Skills. Institute for Fiscal Studies. https://ifs.org.uk/sites/default/files/2023-10/IFS-Green-Budget-2023-Investment-in-training-and-skills.pdf

Tversky, A., Kahneman, D., 1974. Judgment under uncertainty: heuristics and biases. Science 185, 1124–1131. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.185.4157.1124

Widany, S., Christ, J., Gauly, B., Massing, N., & Hoffmann, M. (2019). The quality of data on participation in adult education and training. An analysis of varying participation rates and patterns under consideration of survey design and measurement effects. Frontiers in Sociology, 4, 71. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsoc.2019.00071

Zhao, Q., & Linderholm, T. (2008). Adult metacomprehension: Judgment processes and accuracy constraints. Educational Psychology Review, 20, 191–206. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-008-9073-8